5 Ways to Support Paraprofessionals in the Literacy Classroom

When we begin learning about the science of reading, we spend so much time educating ourselves that the thought of trying to help someone else understand can be overwhelming. We want to use the adults in our classroom wisely, to point paraprofessionals, parent volunteers and the like to purposeful posts during our ELA block, but we are at capacity just getting our lessons planned and we don’t have time to train the eager-to-learn adults in our classrooms.

In today’s blog post, I’d like to make that easier for you by talking about five ways we can support paraprofessionals and other adults in your literacy classroom. When the supporting adults in your classroom have an understanding of these five, you can expect your students to progress faster because your teams will have a common language and understanding around how to support students during a variety of literacy activities.

Without further ado, here are the five:

1. Teach How to Build the Reading Brain

Every supporting adult in your classroom should have a basic understanding of how children learn to read. Guessing words based on context and pictures is deeply embedded in school culture; it’s all we have known for years. Our children are still learning to read this way in some schools, and chances are the adults in your classroom have children who are still being taught to read this way. Here is what you can do to illustrate this process:

Watch the Purple Challenge Video (12 mins). This video shows how a mother learned that leveled books were harming her child. It shows the direct impact of guessing words and how learning how to decode is the needed shift in our instruction.

Explain how our brains are wired to pick up language easily, but that the reading brain needs to be built. Share how our written language system was created by us, and is not something we can just pick up by osmosis. It needs to be taught explicitly.

Share a picture of the brain and discuss how parts of the brain interact when children learn to read. Label the parts of the brain and offer the explanations that follow:

Orthographic processor (eyes): When we look at a word, our orthographic processor activates. Our eyes see the print and our brains search for the unknown word.

Phonological processor (ears): Then, we say the sounds in the word. This activates the phonological processor.

Semantic processor (meaning/context): Next, we blend the sounds in the word, and then our brain searches for the meaning of the sounded out word.

Explain that these three parts of the brain work together when we teach our students the code.

If you need a resource to support you with this, check out The Reading League’s free Science of Reading Defining Guide.

2. Build a Common Language

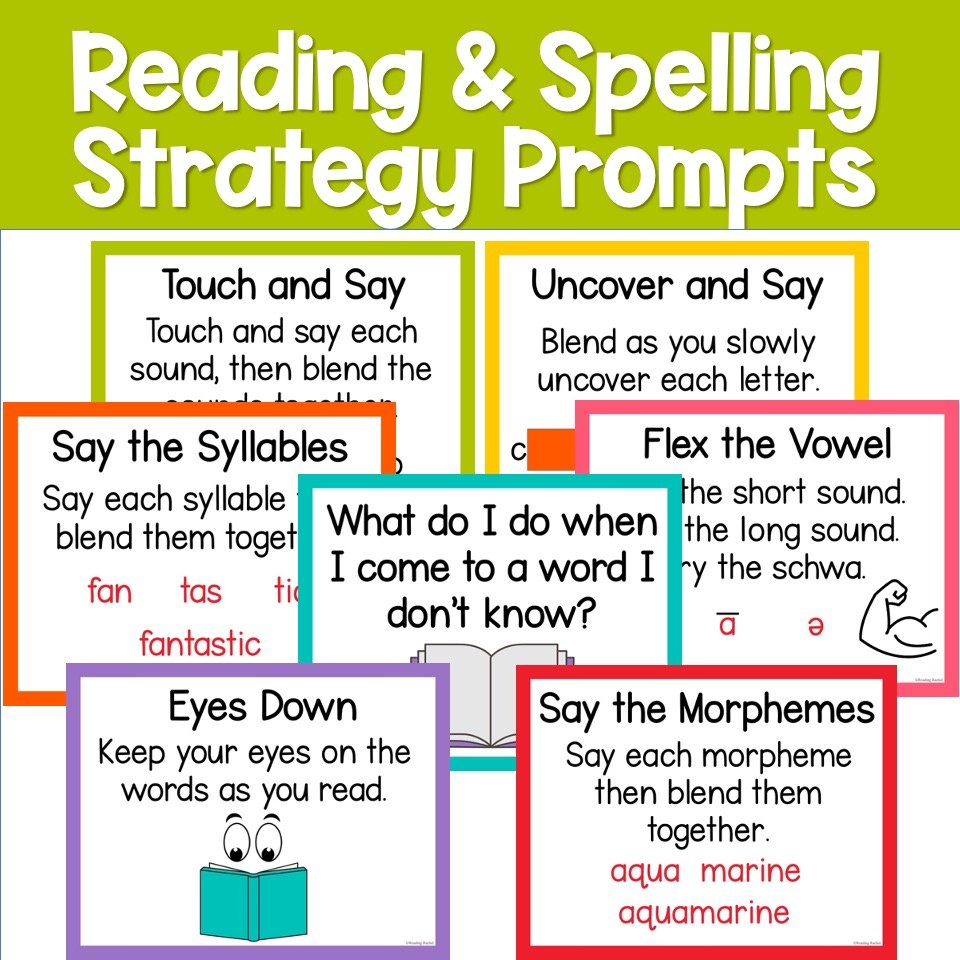

Once your team understands how children learn to read, you can then teach them how to support students when they ask for help while reading and spelling words. I am purposely pointing out reading and spelling words here because it’s these moments where we have a golden opportunity to provide impactful scaffolds for our students. It’s also these moments where we can just as easily perpetuate learned helplessness. If I had a nickel for every time I heard a student say “how do you spell this word?” and the adult replies by dishing out the spelling, I would be rich :). Our struggling readers will continue to struggle if we continue to spoon feed answers to them. Kids need to learn that they can learn. If we just give them the word or tell them the word, we do nothing to build their autonomy. Instead, any adult supporting a student during an ELA block should learn the appropriate scaffolds for helping students read and spell words. This creates a common language across classrooms and a ripple effect on student learning. Here are the ways I encourage adults in my own school to support students with reading and spelling words (the posters pictured are FREE and always will be!):

Reading Strategies:

Keep your eyes on the print as you read.

Touch and say the sounds, then blend them together.

Uncover and say. Cover the word except for the first sound. Say the first sound. Uncover the next letter. Blend the first two sounds together. (/c/, /cl/, /cla/= clap). This is called successive blending.

Say the syllables then blend them together.

Say the morphemes then blend them together.

Flex the vowel. Students should try the short vowel sound, the long vowel sound, and the schwa sound to determine the correct word.

Steps for Spelling Single Syllable Words:

Say the word aloud.

Say the sounds in the word.

Spell the word aloud.

Write the word.

Steps for Spelling Multisyllabic Words:

Say the word aloud.

Count the syllables.

Draw a line for each syllable. For each syllable, write the vowel or vowel team that represents the vowel sound.

Fill in the missing letters for each syllable.

Write the word.

3. Print-and-Go Resources

Using print and go resources as a means of practice for your students supports paraprofessionals because even without extensive background knowledge on teaching reading, some resources are easy to use and understand. Extensive practice is often a missing link in an effective ELA block. Students need practice! The key is knowing what skills your students can practice independently because they have already been taught the skills. We don’t want to give students (or supporting adults) new skills to learn. The practice piece should always reflect skills that have been previously taught. If you need a print and go resource to support you, my phonics review packs include a “how to” for each review activity, and I specifically made these to be used by paraprofessionals, parent volunteers, and any other adult pushing in during a reading block.

4. Teach How to Give Feedback

In addition to building a common language so that appropriate scaffolds may be given to students, teaching adults how to give feedback to students is important. It’s also an easy way to improve reading outcomes. Corrective feedback has been affirmed throughout research to increase learning outcomes (Hattie & TImperly, 2007; Lenz, Ellis, & Scanlon, 1996; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996; Stronge, 2002; Marchand-Martella et al. 2004). Which means, if you teach your supporting adults how to do this, your students’ reading outcomes will be improving while you are off working with a small group at your table.

There are three types of feedback we can give:

Affirmative: This is when we give students specific praise. We tell them what they did well so that they can repeat it in the future. Here are some examples:

Reading & Spelling Words:

I love how you realized you made an error and went back and read the word correctly.

That was excellent. It really helps us become better readers when we try a different vowel sound to get to the correct word.

I love the way you tapped the sounds in that word to help you read it correctly.

Great! I knew you could do it. Keep doing it; going back and rereading the sentence after we make an error helps us read more fluently.

I love how you looked for morphemes before you tried to read that tricky word.

I love the way you said each sound before you spelled the word. That helps us spell the word correctly.

Great job breaking that word down into syllables. That helps us spell the word part by part.

Yes. Excellent. Always say the word aloud before you try to spell it. That helps us hear all the sounds so we don’t miss any letters.

Informative: This is where we explain areas of improvement.

Fluency: Can I give you some advice that will help you for next time? Read this next sentence like you are talking and having a conversation with me.

B/d confusion: Make a B with your left hand and see if it matches the B you just wrote. Let’s fix that D and change it to a B. Start at the top, tall line down, up and around. Any time you are unsure if it’s a B or D, use your “B hand” to check.

Skipping words: on the next paragraph I want you to use your pointer finger and track the words as you read. Make sure your finger stays under the word you are reading as you read. This will help make sure we don’t miss any words!

Word Reading Error: Let’s go back to that word. Touch and say the sounds. What’s the word? Remember to always say the sounds if you come to a word you don’t know.

Vowel Sound Confusion: Let’s go back to that word. Check your vowel sound. What’s the word? Remember to check your vowel sound if you can’t figure out the word. Try the short sound, long sound, and the schwa.

Corrective: This is where we directly tell students what we need them to know in order for them to be successful.

Word Reading Error- The SH in that word spells the /sh/ sound. Read it again and say /sh/ when you see SH.

Spelling Error- The /ch/ sound is spelled with CH. Write CH.

Fluency: Watch me read this sentence, then repeat it back to me and see if you can match my expression and read it exactly the same way as I did.

5. Read, read, and read more connected texts (and read more)................and more.

We don’t talk about this enough. Our students need practice applying the phonics skills they are learning in real text. This is the muscle they need to flex to grow as readers. Fluent word readers do not equal fluent text readers. This is the absolute most important part of the phonics component of your literacy block. Kids need practice reading in texts, and they need either a partner or an adult providing them the corrective feedback mentioned above.

The type of text to use for connected text depends on the grade level you teach:

Kindergarten: Decodable words and sentences

1st Grade: Decodable passages/books

2nd Grade: Decodable & non-decodable passages and books

3rd Grade & Beyond: Non-decodable passages and books

These grade level specific suggestions are not based on evidence; this is my opinion. The type of text you choose also depends on your students, not necessarily the grade level. You might have a significant amount of high flyers in your first grade classroom who are ready to read non-controlled books. Let them! You can still use decodable books during instruction and for practice, but layer in those non-decodable books.

When students read connected text, they develop the flexibility required to decode unfamiliar words. And, most importantly, they learn how to use their decoding and comprehension skills simultaneously.

Finally, reading one decodable text each day is not enough. Give adults in your classroom passages that students can reread while they sit and provide the feedback mentioned above.

Well, there you have it. Those are my top five tips for supporting paraprofessionals with the science of reading. The key to improving student reading outcomes is to build a common understanding throughout your building, and it starts with the people in your classroom working directly with students.